Books

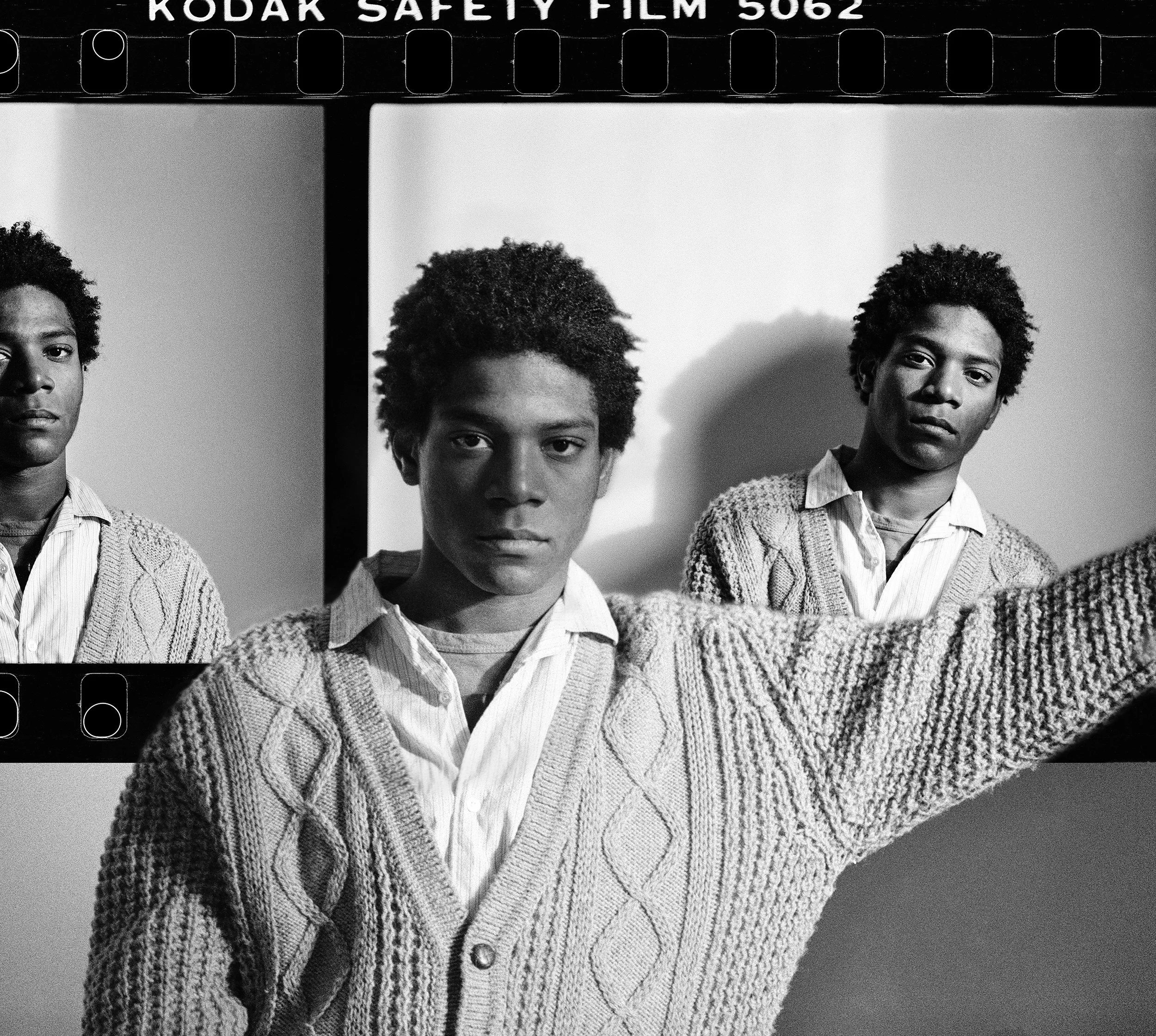

Jean-Michel Basquiat King Pleasure©

Exhibition Catalog

by Lisane Basquiat , Jeanine Herveaux, et al.

This landmark volume tells the story of Jean-Michel Basquiat from the intimate perspective of his family, intertwining his artistic endeavors with his personal life, influences, and the times in which he lived. Organized by Jean-Michel's family, the exhibition and accompanying catalog feature over 200 never-before and rarely-seen paintings, drawings, ephemera, and artifacts across 318 pages.

Basquiat’s contributions to the history of art and his exploration into our multi-faceted culture—incorporating music, the Black experience, pop culture, African American sports figures, literature, and other sources—are showcased alongside personal reminiscences and firsthand accounts providing unique insights into Basquiat’s creative life and his singular voice that propelled the social and cultural narrative that continues to this day.

// Purchase

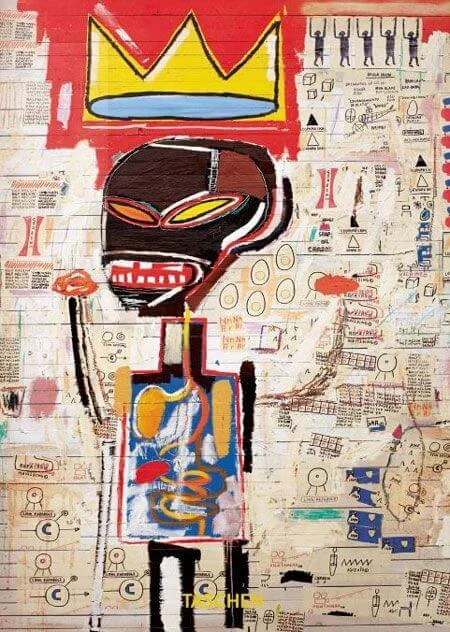

Jean-Michel Basquiat

by Eleanor Nairne (Author), Hans Werner Holzwarth (Editor)

This acclaimed Taschen monograph offers a vivid, immersive look at Jean-Michel Basquiat’s life and work. Spanning nearly 500 pages, it features striking large-format reproductions of his paintings, drawings, and notebooks. Curator Eleanor Nairne’s essays, alongside editor Hans Werner Holzwarth’s contextual framing, guide readers through Basquiat’s evolution—from his early days as SAMO to his rise in the 1980s New York art scene.

Set against the backdrop of downtown Manhattan’s cultural explosion, the book explores Basquiat’s signature use of language, symbolism, and social critique. With references to jazz, literature, identity, and power, it captures his layered visual language while weaving in his own words and critical responses. The result is an accessible, authoritative portrait of a singular artist who transformed contemporary art. // Purchase

Jean Michel Basquiat, Hardcover

by Enrico Navarra (Author)

This two-volume collection offers the most expansive look at Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work to date, featuring over 900 full-color images across 686 pages. Edited by Enrico Navarra, it combines critical essays and personal stories from those who knew Basquiat best—including Johnny Depp, Annina Nosei, Tony Shafrazi, and Diego Cortez—capturing the raw intensity and cultural urgency of his art.

From his early days as SAMO to his rise in the global art scene, the book explores Basquiat’s bold use of language, symbolism, and social commentary. His work is framed within the broader context of race, identity, and power, making this volume both an essential academic resource and a deeply human portrait of a visionary artist. // Purchase

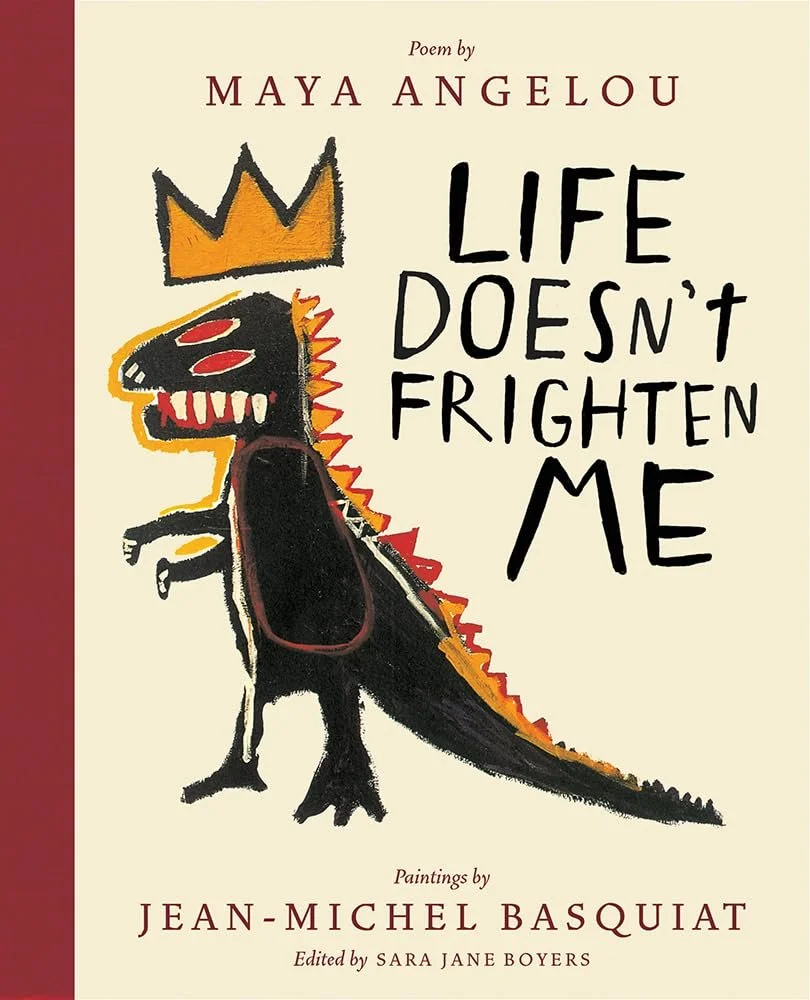

Life Doesn't Frighten Me: A Poetry Picture Book

by Maya Angelou (Author), Jean-Michel Basquiat (Author), Sara Jane Boyers (Author)

This celebrated picture book brings together the fierce, lyrical voice of Maya Angelou and the dynamic visual language of Jean-Michel Basquiat in a fearless tribute to inner strength. Life Doesn’t Frighten Me pairs Angelou’s iconic 1993 poem with Basquiat’s bold, expressive artwork—capturing the emotional highs and lows of childhood with raw honesty and imagination.

Whether facing shadows, bullies, or the unknown, Angelou’s rhythmic refrain becomes a powerful mantra of resilience. Basquiat’s art channels the energy and chaos of fear, while also revealing the strength it takes to rise above it. With added biographies and an afterword by editor Sara Jane Boyers, this book serves as both an introduction to poetry and a gateway into the world of contemporary art—a stirring reminder that courage lives inside us all. // Purchase

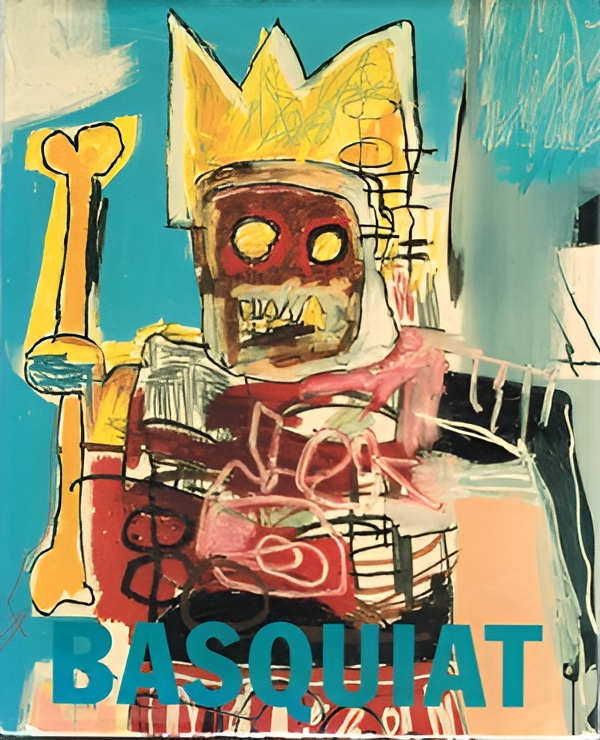

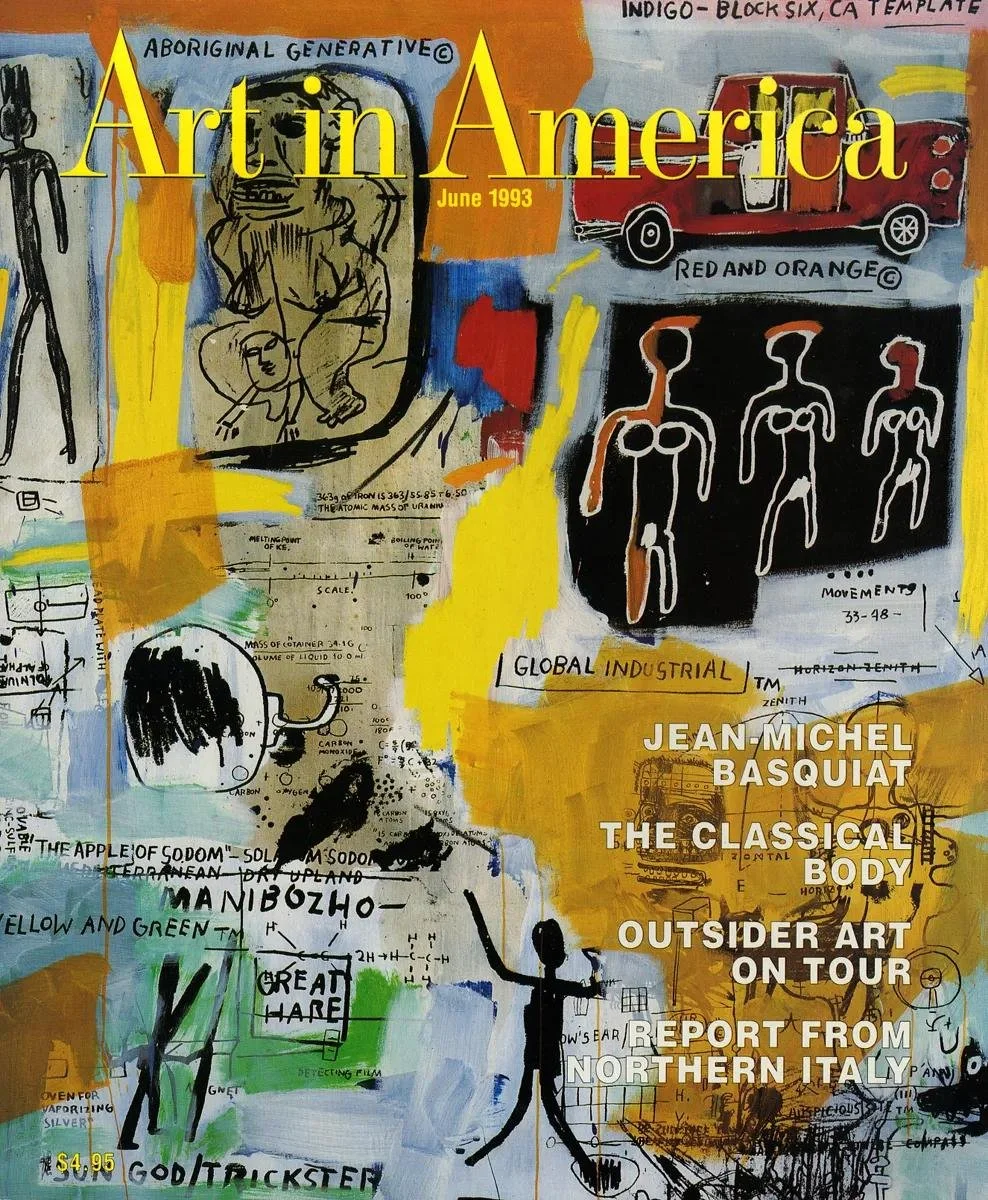

Jean-Michel Basquiat

Essays by Dick Hebdige, Klaus Kertess, Richard Marshall, Rene Ricard, Greg Tate, and Robert Farris Thompson

This landmark volume, published in conjunction with the Whitney Museum’s 1992–93 retrospective, brings together the voices of six influential critics to explore the force and complexity of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work. Through essays by Dick Hebdige, Klaus Kertess, Richard Marshall, René Ricard, Greg Tate, and Robert Farris Thompson, the book traces Basquiat’s trajectory from downtown graffiti artist to cultural icon—an artist whose canvases challenged the white-dominated art world with their explosive energy and coded visual language.

Each contributor offers a distinct lens: Ricard captures Basquiat’s poetic mystique; Hebdige and Tate unpack the artist’s collision of race, power, and media; while Thompson connects his visual vocabulary to African diasporic traditions. Together, they illuminate how Basquiat fused street culture, art history, and lived experience into a body of work that defies easy categorization. The result is a dynamic, multi-dimensional portrait of an artist who, in a brief and blazing career, redefined what painting could be—and for whom it could speak. // Purchase

Jean-Michel Basquiat (Tony Shafrazi Gallery)

by Peter M. Brant, Jeffrey Deitch, Henry Geldzahler, Keith Haring, Ted Joans, Glenn O'Brien, Francesco Pellizzi, Herb and Lenore Shorr, and Franklin Sirmans.

Published in conjunction with a major retrospective at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery, this monograph offers a wide-ranging portrait of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s creative journey. It features over 200 color and black-and-white illustrations and a detailed chronology that traces the arc of his prolific, all-too-brief career.

The volume brings together essays by artists, curators, critics, and close collaborators—including Tony Shafrazi, Gerard Basquiat, Jeffrey Deitch, Glenn O’Brien, Keith Haring, and others—each offering unique insight into Basquiat’s cultural impact and artistic legacy. Combining visual depth with personal reflection, the book stands as a compelling tribute to the artist’s enduring influence. // Purchase

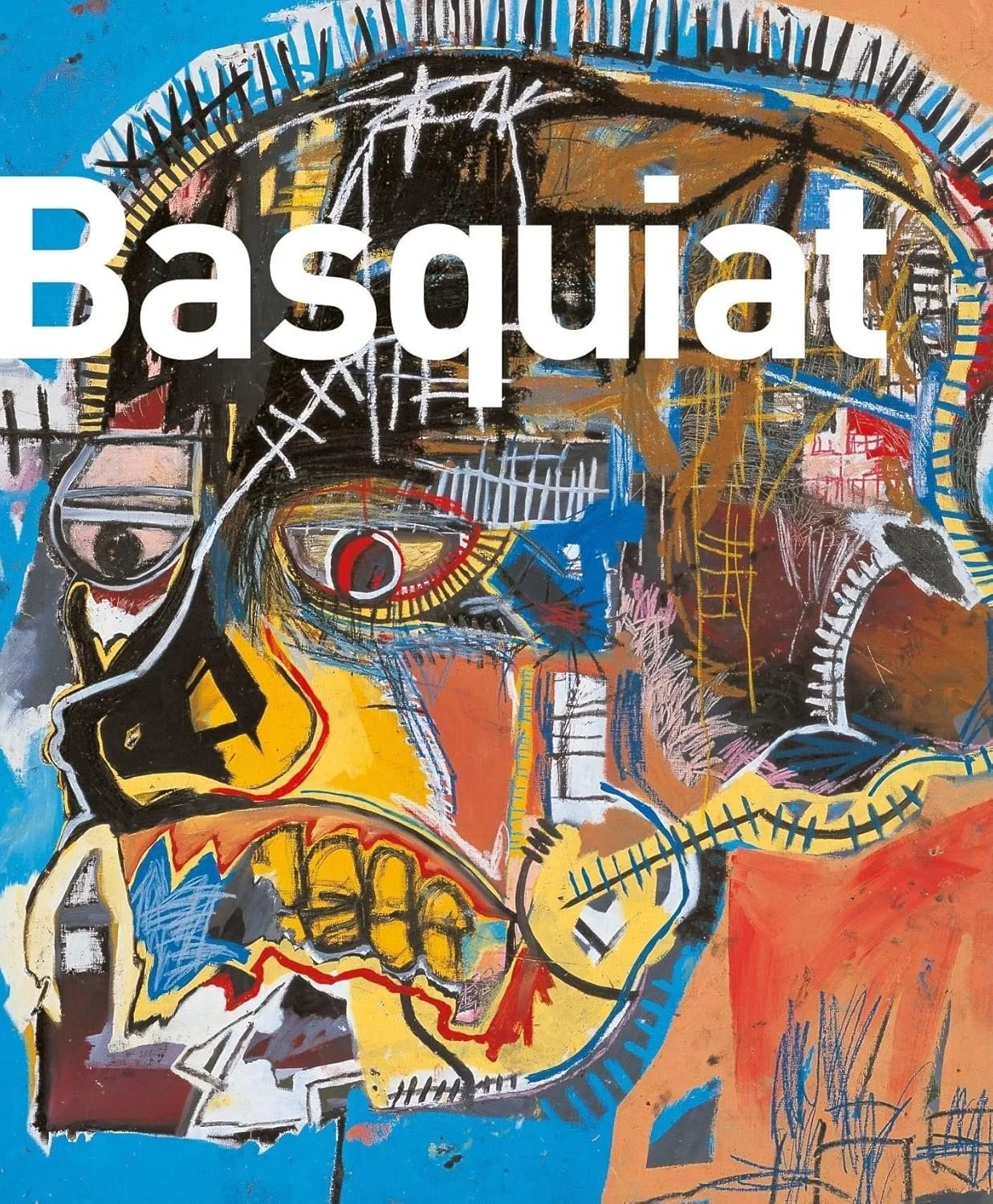

Basquiat, Paperback

by Fred Hoffman (Compiler), Kellie Jones (Compiler), Franklin Sirmans (Compiler), Marc Mayer (Editor)

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s rise in the art world was as explosive as it was brief. Born in Brooklyn in 1960, he moved from street art notoriety to international acclaim in less than a decade. This volume revisits that transformation, centering on the force of Basquiat’s creative output rather than the mythology that often surrounds him. Through a focused lens on his most pivotal works, it reveals how Basquiat redefined contemporary painting by fusing street culture, historical references, and personal symbolism.

With vivid reproductions and critical insight, the book highlights Basquiat’s fierce engagement with race, power, and identity—offering a deeper understanding of his language of crowns, skulls, and fragmented text. Set against the backdrop of 1980s New York, it captures not just the energy of a movement but the singular voice of an artist who continues to shape the conversation in art and culture. // Purchase

New York Beat: Jean-Michel Basquiat in Downtown 81

by Glenn O'Brien, Photographs By Edo Bertoglio and Maripol

New York Beat: Jean-Michel Basquiat Downtown 81 is a rare visual diary, published exclusively in Japan, chronicling the making of the semi-documentary film Downtown 81 (originally titled New York Beat). Spanning 111 pages, the book pairs Edo Bertoglio and Maripol’s candid photography with Glenn O’Brien’s reflective text in both English and Japanese, offering a raw, firsthand look into Basquiat’s world during the winter of 1980–81.

Shot across the streets, clubs, and lofts of downtown Manhattan, the imagery captures Basquiat before fame—riding subways, painting walls, and interacting with fellow creatives from the city’s vibrant underground scene. O’Brien’s writing situates these visuals within the cultural energy of the time, highlighting the intersection of art, music, fashion, and rebellion. More than a companion to the film, the book stands as a time capsule and a tribute to a young artist navigating and shaping the creative chaos of New York in real time. // Purchase

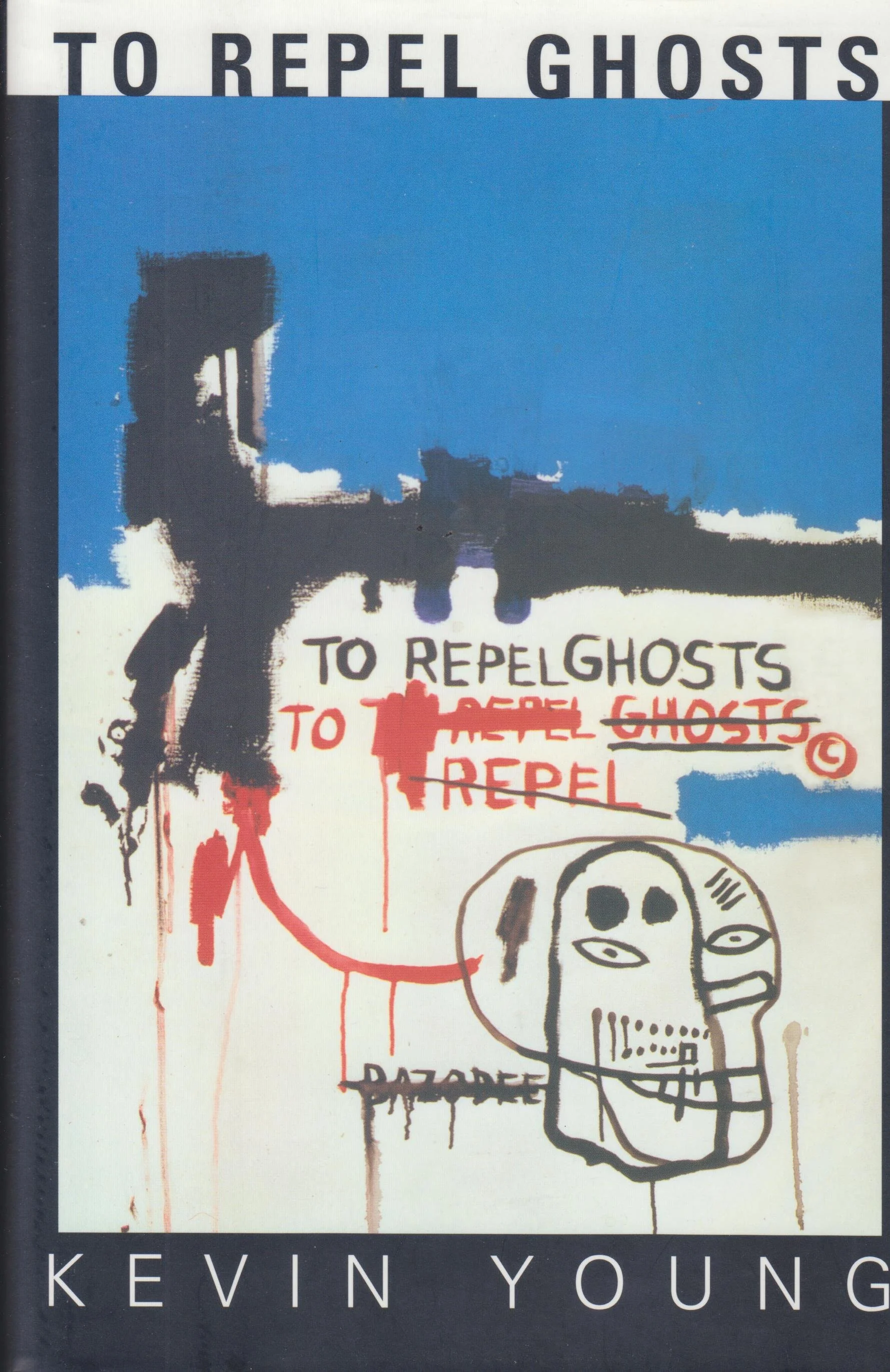

To Repel Ghosts: Five Sides in B Minor

by Kevin Young (Author)

To Repel Ghosts is a genre-bending tribute to Jean-Michel Basquiat—part biography, part mixtape, and fully alive with rhythm and reverence. Poet Kevin Young takes Basquiat’s life and art as both subject and structure, composing a double-album in verse that riffs on the artist’s signature blend of color, language, and Black cultural memory. Like Basquiat’s canvases, the poems move with improvisational energy—funk, jazz, hip-hop, and spirituals all bleeding together to echo the artist’s layered world.

Split into two “discs” and five “sides,” the book mirrors a vinyl album, honoring Basquiat’s musical influences and his fast-burning career—from the raw graffiti of SAMO© to the pressures of sudden fame. Along the way, Young pays homage to other icons—Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, Grace Jones, Robert Johnson—casting Basquiat’s story as one among many in a lineage of Black brilliance and struggle. The result is an epic chorus of voices and visions, each track amplifying Basquiat’s defiant, dazzling legacy. // Purchase

Essays

Altars of Sacrifice: Remembering Basquiat

by Bell Hooks

In this powerful 1993 essay, bell hooks examines Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work as a profound act of personal and cultural sacrifice. She argues that his art can be seen as ritual offerings—fragments of selfhood that had to be silenced or reshaped to survive in a predominantly white art world. Through this lens, Basquiat’s canvases become sites of tension, where identity, erasure, and expression collide.

Hooks also critiques how white critics often misread Basquiat’s work, labeling it “primitive” or derivative through a Eurocentric lens. She calls for a broader, more inclusive understanding—one that recognizes the layered energy in Basquiat’s fusion of Afro-Caribbean roots, urban street culture, and modernist technique. By reframing the narrative, hooks reveals the radical power and complexity in Basquiat’s voice—and why it still demands to be heard. // Read more

The Defining Years: Notes On Five Key Works

By Fred Hoffman

In this essay, Jean-Michel Basquiat emerges as a visionary who filtered the chaos of his world into distilled, symbolic expressions of personal and societal truth. First known as SAMO, his early text-based street art gave way to deeply introspective works exploring spiritual themes, mortality, and Black identity. From Untitled (Head) to La Colomba, Basquiat painted dualities: God and law, life and death, Black and white, the external world and inner consciousness. His signature motifs—crowns, halos, torches—were not decorative but deeply encoded signals of transcendence and self-assertion.

In Acque Pericolose, he confronts mortality with dignity. Per Capita shifts focus to economic disparity and heroic identity. Notary reveals his psychic anguish at the peak of fame, while La Colomba depicts his surrender and spiritual integration. Across these works, Basquiat collapsed binaries and redefined portraiture as a map of inner life. Rather than mythologize the artist, this essay underscores how Basquiat used image, text, and form to pursue a higher truth, creating art that continues to resonate with emotional and intellectual urgency. // Read more